|

The Wall

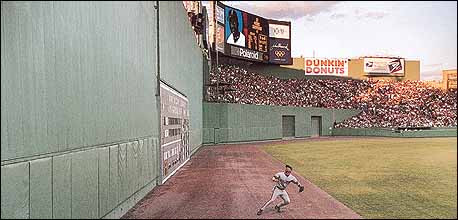

Whatever lies ahead for Fenway Park, left field's Green Monster will stand as a monument to baseball

|

The Wall is worshipped by hitters, feared by pitchers, and alternately mastered

and butchered by outfielders who want to play unconventional caroms.

This article is excerpted from a book by Shaughnessy and Grossfeld entitled

'Fenway: A Biography in Words and Pictures,' to be published this month by Houghton Mifflin.

[ Signed copies ]

|

Text by Dan Shaughnessy

[ Photographs ] by Stan Grossfeld

It is a New England landmark, no less so than the Bunker Hill Monument, the Old Man of the Mountain, or Walden Pond. And when Major League Baseball is no longer played in Fenway Park, there is a good chance that the left-field wall will be preserved, either as part of the next park or as a monument to the first century of American League baseball in Boston.

It was built to keep baseballs in play, but its beauty is the memory of all the balls that have sailed over it. No one knows when the left field wall was first called the Green Monster, but it stands as the signature feature of this singular baseball park.

It is probably the Wall's appeal to young people that explains its lasting fame. A 6-year-old at his or her first big-league game might walk into Camden Yards in Baltimore, Jacobs Field in Cleveland, or even Yankee Stadium in the Bronx and never remember anything specific about the park itself. But a little kid going to his or her first game in Boston is sure to remember the first breathtaking glance at the huge wall in left field. It's big and green and unlike any facade in professional sports. Children remember the Green Monster the way they remember their first look at the Grand Canyon or the Golden Gate Bridge. Size matters. The Green Monster is impossible to ignore or forget.

More than any quirky feature, the Wall has come to symbolize and encapsulate the Fenway experience. The Boston Garden had its parquet floor (which has been moved to the FleetCenter), Wrigley Field has ivy-covered bricks in the outfield, and Notre Dame football is played in the shadow of the Golden Dome under the watchful eye of Touchdown Jesus, but Fenway's Wall is the most identifiable feature of any sports venue in America.

When network television cameras broadcast a Red Sox game across the country, fans in Des Moines see the Wall and instantly know that the game is being played in Boston. It's like hearing the chowder-thick accent of Ted Kennedy on a newscast. It's everything Boston.

The Wall is a larger part of Boston's baseball history than Ted Williams or Carl Yastrzemski. It is worshiped by hitters, feared by pitchers, and alternately mastered and butchered by outfielders who want to play its unconventional caroms. Managers have lost their hair trying to make the Wall work in their favor, and too many pitchers and hitters have changed their natural practices in an attempt to take advantage of what the Wall offers and denies.

Fenway's left field wall is 37 feet high and capped by a 23-foot screen that prevents balls from peppering the pedestrians and vendors on Lansdowne Street. The Wall is 240 feet long and was originally constructed from 30,000 pounds of Toncan iron in 1934. Its reinforced steel and concrete foundation sinks 22 feet below the field.

Signs advertising whiskey, razor blades, and soap covered the Wall for more than 10 seasons before it was painted green in 1947. Today, Monster Green is a custom blend made by John Smith, a commercial painter in Wilmington, who inherited the job from his father, the late Ken Smith. The initials of former owners Thomas A. Yawkey and his wife, Jean, are set in Morse code on its scoreboard. The Wall was rebuilt in 1976: Old tin panels were replaced by a Formica-type covering that yielded more consistent caroms and less noise. (The tin panels were cut into small squares and sold; the proceeds went to the Jimmy Fund.) When the old Wall was in place, batting practice shots in an empty Fenway produced a clang; now it's something closer to a thud.

At the foul pole, the Wall is only 309 feet and 3 inches from home plate, but for most of the century the Red Sox posted a sign that read ``315.'' Club officials refused to allow anyone to measure the real distance, but when

The Boston Globe snuck into Fenway and came up with the new figure, the Sox grudgingly changed the sign. Major League rules today stipulate that no fence in any new park be closer than 325 feet to home plate, but this will probably be waived if the Sox choose to duplicate the Wall in their next park. The term ``grandfather clause'' was invented for Fenway Park.

The Wall's massive dimensions make it appear closer than it is, and that, too, is part of its appeal. Baseball fans are dreamers, and most of them played a little hardball in their day. Is there a healthy male in his 20s, 30s, or 40s who doesn't believe he could stand in Fenway's batter's box and line a couple of shots off or over the Green Monster?

One of baseball's last hand-operated scoreboards is inside the Wall. There, a few part-time Sox employees slide 2-pound, 12-by-16-inch numbers into slots to tell fans how the Sox are doing and how things are shaping up around the American League. When there's a pennant race and fans are rooting for the Sox to overtake the Yankees, there can be quite a bit of suspense when the kids behind the green door take down a zero and put up a number to show them that the Orioles have just scored against New York in Yankee Stadium. No electronic message board can duplicate this thrill.

Inside the Wall there is no permanent bathroom, although portables have been used. It's dark, dirty, and designed for Quasimodo. Rat poison lines the floor. It's boiling in the summertime and freezing in the spring and fall. But the kids get to talk with opposing left fielders, and Ted Williams says some of his favorite Fenway memories are chats with the faceless, Oz-like people behind the scoreboard. Tours of Fenway were instituted in the 1990s, and fans are allowed to duck into the room in the Wall. Some of the graffiti are pretty rough, but if you look hard enough, you may find signatures from members of the ground crew and American League players of the last half-century. Walk into this sanctuary and the first thing you see are the names of Wall workers Dave Savoy, Jim Reid, and Billy Fitzgerald under the heading ``1961 All-Star Game.'' One can only presume that these three young men manned the big board for the midsummer classic during the John F. Kennedy administration.

``I worked inside the Wall for a couple of summers,'' recalls Joe Cochran, the equipment manager of the Red Sox. ``Not every night, but enough games to know what it's like. One night it was so hot, I wound up working in just my boots and boxer shorts. There's drainpipes out there, and I used to see rats' noses poking through. We had a portable toilet, so that helped. Later, when I'd be in the dugout with the team, I'd call to the scoreboard and tell them the Yankees or Tigers just got 10 runs in the first inning. The poor kid would post the 10 and the whole crowd would groan.'' In 1975, the late NBC-TV director Harry Coyle put a camera inside the left field wall. Legend has it that during the first game the camera was used in, a rat appeared, which froze the camera operator and resulted in the best baseball video clip of all time. The unattended camera was focused on home plate and caught Carlton Fisk waving his arms, willing his fly ball into fair territory. His drive caromed off the left field foul pole, and NBC was rewarded with a clip capturing what TV Guide in 1998 ranked as the greatest moment in the history of sports television.

There are plenty of other signatures inside the Wall. John Stone and John Giuliotti of the ground crew signed while working the 1986 World Series. To the right of their signatures is the autograph of Jimmy Piersall, a master defensive outfielder and base runner for the Sox in the 1950s. He became famous when his biography, Fear Strikes Out, was made into a major motion picture, starring Anthony Perkins. Other graffiti indicate that somebody inside the Wall logged the home runs hit by Ted Williams in 1951 (there were 30). There's a signature from Dennis ``Oil Can'' Boyd - ``The Can'' - and a marking from pitcher Boo Ferriss, 1945-50. There are even graffiti from the turbulent '60s: ``Free Angela'' and ``Stop the War.''

According to Joe Mooney, the Sox groundskeeper, the Wall is a fine conductor of heat. When Fenway was buried in snow on April Fool's Day 1997 (while the Sox were opening the season on the West Coast), Mooney piled snow up against the Wall, claiming it melted faster that way.

For decades, the Wall has artificially inflated the numbers of Boston's right-handed batters and encouraged the Red Sox to field a team of slow, big-swinging, righty sluggers. Assembling this kind of team has been done at the expense of speed and fundamentals. The Wall teaches a manager to eschew the bunt, forget the hit-and-run, and wait for the game-breaking, three-run homer. It has scared generations of left-handed pitchers, and rare is the southpaw who will pitch inside at Fenway (the last Red Sox lefty to win 20 games was Mel Pamell, in 1953). The Wall has encouraged the Red Sox to design teams that have trouble winning away games; historically, the Sox have been embarrassed on the artificial turf of Kansas City and also in Yankee Stadium, where left field is several acres larger than in Boston. The 1949 Red Sox went 61-16 at home but only 35-42 on the road, losing the American League pennant in New York when they dropped the final two games of the season.

Many Sox fans believe that the Wall was the undoing of George Scott in 1968. Scott hit .303 during the Impossible Dream season of 1967 but a year later dropped to .171, with three homers. Ask Sal Bando what it did to him during the 1975 American League Championship Series. In the second game of the playoffs, at Fenway, Bando hit four shots off the Wall; at least a couple of them would have been homers in most other ballparks. Bando's harvest was 2 singles and 2 doubles.

American League outfielders have been confounded by the Wall for more than 60 years. There can be little doubt that Carl Yastrzemski was the master of Wall-ball defense. Yaz could decoy better than any outfielder and routinely pretended he was ready to catch a ball that he knew was going to carom off the Wall. Sometimes this would make runners slow down or stop altogether. Yaz had another Wall habit that annoyed some Boston pitchers. When a slugger unloaded on a meatball from a Sox hurler, Yaz would sometimes stand motionless, hands on hips, staring forward as the ball sailed over his head, over the screen, and out toward the Mass. Turnpike. He didn't want to give the hitter the satisfaction of turning around, and sometimes it was a message to a Boston pitcher who may have thrown the wrong pitch to the wrong guy.

``I knew when the ball was going out,'' said Yastrzemski. ``lt was something I worked into the decoy. But it used to tick the pitchers off. Bill Monbouquette used to say, `Can't you at least make it look like you can catch it?'''

Jim Rice followed Yaz to the left field pasture in 1975 and suffered from comparisons with the Hall of Famer. Rice never got better than average defensively, but he did learn the Wall and its caroms, which give visiting outfielders fits. Earl Weaver, the former Orioles manager, still laughs at the thought of Baltimore left fielder Don Baylor trying to play the Wall when the O's came to Boston. Baylor once got tangled up in the left field corner, trying to corral a ball that was rattling around the doorway in the corner, and men in the Orioles dugout (which has no view of the corner) wondered what had happened as they watched the Red Sox runners going around the bases. It was one of those ``only in Fenway'' moments.

The Wall has a ladder that enables the ground crew to retrieve home run balls that are caught in the screen above it. It's the only fair-territory ladder in the majors. One night in the '50s, Ted Williams and Jimmy Piersall converged under a fly ball in left center field. To their surprise, the ball hit the ladder and ricocheted toward center, allowing Jim Lemon to circle the bases for an inside-the-park homer. Another one of those moments came in 1963, when the Sox stonefinger slugger Dick Stuart - a man with all the speed of an ox - hit an inside-the-park home run in Fenway. His towering fly to left center hit the ladder, then bounced off the head of the Cleveland center fielder, Vic Davalillo, and rolled to the left field corner. By the time Davalillo ran down the ball, Stuart had chugged around the bases.

The Wall has made heroes out of hitters like Walt Dropo, Stuart, Tony Conigliaro, Rico Petrocelli, George Scott, Ken Harrelson, Rice, Butch Hobson, Tony Perez, Tony Armas, and Dwight Evans. It has helped the Red Sox draw fans and boast of home run champions. It has created excitement and memories, but it has hurt the Red Sox by artificially inflating the abilities of the ball club. It has tipped the scales of baseball's balance, distorting the product and creating advantages and disadvantages that are patently unfair. Never was this more obvious than on the afternoon of October 2, 1978, when Bucky Dent hit a weak pop-up that plopped into the screen and forever changed the course of Red Sox history.

Dent's home run beat the Red Sox in the infamous one-game playoff of 1978, denying the best Boston team of the last half-century its chance to compete in the post-season. It's a cruel joke that a sawed-off shortstop representing the New York Yankees would be the one to use the Wall like no other player in baseball history.

|

![]() Click here for past issues of the Globe Magazine, dating back to June 22, 1997

Click here for past issues of the Globe Magazine, dating back to June 22, 1997![]()