Local Chefs

Local Chefs

From Ming Tsai (above) to Todd English, hit television. |

s 1998 slips away and the last year of the millennium waits in the wings, it's time to review the year in dining. Americans, in particular Bostonians, obsessed about restaurants this year, talked about them, complained about them, praised them, and anticipated each new entry in the city's pantheon of dining.

s 1998 slips away and the last year of the millennium waits in the wings, it's time to review the year in dining. Americans, in particular Bostonians, obsessed about restaurants this year, talked about them, complained about them, praised them, and anticipated each new entry in the city's pantheon of dining.

This was the year of the ubiquitous chef. Chefs have been part of Boston's celebrity circuit for several years, but '98 marked an explosion of chefs in the public eye and culinary publicity. It used to be that the chef was in the kitchen and the rest of us were out front. Now the diner can't escape the chef. Area chefs such as Ming Tsai of Blue Ginger and Todd English of Olives and Figs stared at us from the television set; others talked to us on radio shows. Chefs such as Susan Regis of Biba and Stan Frankenthaler of Salamander gave food demonstrations at Macy's and at seemingly every grocery store in the Commonwealth. Others spoke out against irradiation and genetically altered plants, and cham-

pioned local farmers. They lectured schoolkids about nutrition and jetted off to Jamaica to discuss computer use in underdeveloped countries.

No smoking

No smoking

The cigarette is stubbed out in Boston restaurants. |

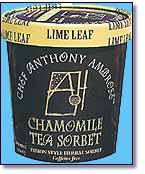

Chefs even came into our kitchens by way of their retail products. Several local chefs began selling their wares in supermarkets and specialty food stores. The home cook gained a window into restaurant kitchens with English's frozen pasta and sauce, chamomile tea sorbets from Anthony Ambrose of Ambrosia on Huntington, and the Galleria Italiana owners' pasta sauces and olive oils.

Dining out in '98 took on a Gallic cast as we ate French at the bistros, cafes, and brasseries that popped up like mushrooms after a hard rain. After years of honing our pasta identification skills - ''Yes, dear, I'm sure the curly kind is fusilli'' - we had to retrain our tastebuds in escargots and frogs' legs. Rillettes and choucroute, steak and frites, and profiteroles flooded the menus. Unlike the early wave of haute cuisine and haughty French waiters in the '60s and '70s, this breed of restaurant is more earthy with hearty food and casual (read American) service.

All that French brought back old dishes with a retro fury. Terrines and pates graced many appetizer menus, French and beyond. Silky smooth and unctuous, or rough-textured and studded with duck confit or pistachios, they were so good we wondered why we had given them up. Maybe it's time to hunt for that ceramic mold in the back of the pantry.

Butter's back

Butter's back

On the table as the perfect accompaniment to bread. |

Butter bounced back, too, regaining all the ground it lost earlier in the decade to olive oil on restaurant tables. Diners could be seen liberally smoothing it over crusty bread, satisfied smiles crossing their faces, calorie-counting cast to the winds. Just a year ago or so, one still had to ask for butter as the olive oil dish was passed around. Now a stubborn friend of mine has to repeatedly request olive oil, even in North End eateries.

It's really not surprising that as we hurtle toward 2000, the fin-de-siecle tendencies are rampant. ''Bring on the best, the richest, the most decadent of food and drink,'' we seem to be saying - or at least that's what the restaurants think we're saying. Foie gras with fruit, foie gras mousse, foie gras melted inside roasted halibut. Truffles in pasta, truffles in pate, truffles galore. Champagne sauces and triple creme cheeses and puff pastry cages around nuggets of, well, foie gras and truffles. If the next year shapes up at all like this one, the 21st century will find us satisfied but awash in cholesterol.

On the healthy side of the ledger, Boston's restaurants went smoke-free by decree of the city. After dire warnings about how the ban would affect businesses, there was no firestorm of protest as the smokers huddled around the bar after their meals.

Green

Green

Overtakes yellow as the color to splash on restaurant walls. |

Dining at the bar was in anyway, the place to be for a quick bite at the Blue Room before the movies or the spot to be spotted at Oskar's or Brasserie Jo. Barside meals were perfect for eating raw everything - tartares of tuna or scallops or steak, all prodded by the spreading popularity of sushi.

The game bird of the year was quail, diminutively appealing and glazed deep brown on mushroom risotto, with grapes or figs, in caramelized sauces and in pomegranate molasses. And when quail wasn't the focus, tiny poached quail eggs were the accent point atop the foie gras or floating in soups.

Caramelizing was the technique of the year. Once part of the dessert repertoire, caramelizing moved over the line into savory dishes, minus the sugar. Onions were caramelized, fish got a golden film of carmelizing, lamb shanks were deeply caramelized. And on the dessert side, plates were crisscrossed by caramel, sometimes so much of it that the diner's teeth stuck together.

As the dessert fork, once the proper tool for the end of the meal, went into hiding, we maneuvered spoons. The spoons were handy to scoop up ice cream, custard, and creme brulee, all the rage in '98, but didn't work too well on pastry crusts - and also made diners feel they were back in the nursery.

Farmers

Farmers

Getting credit on menus; their greens get star treatment on the plate. |

We were soothed, though, by green. Celadon, spring green, pale chartreuse, and cool greens tempered with blue - it was the new color, pushing hot yellows out on the street. Most restful, but the news out of New York City is that white is in, so look for paintbrushes to be out again.

Speaking of greens, formerly anonymous salad ingredients and other produce received special billing on menus, recognizing such growers as Nesenkeag Coop Farm and Verrill Farm.

Of course, the New York influence always catches up with us, most noticeably here in portion size. After Boston diners got used to plates groaning with enough food to feed a family of four, chefs have pared down. Now, following the lead of the big city, entrees look more sophisticated but barely cover the middle of the oversized plates used in the top-tier restaurants. And appetizers - sometimes one needs binoculars to spot them. Diners accustomed to generous doggie bags grumble, but fashion rules and the fashion dictates less is more.

The infant 1999 may be the dawning of a new dining trend, the tasting menu. In rarefied restaurants like Charlie Trotter's in Chicago and the French Laundry in Yountville, in California's Napa Valley, diners put themselves in the chef's hands and out flows five to nine tiny and intricate courses - the ultimate less is more. Chefs in New York City are experimenting with just tasting menus. A few in Boston, such as Frank McClelland at L'Espalier and Gordon Hamersley at Hamersley's Bistro, offer a streamlined or occasional version of the tasting menu.

Chefs go retail

Chefs go retail

Products like Anthony Ambrose's sorbet are now widely available. |

As more of this city's chefs reach star status and the economy hums along, someone will take the chance that they can sell a tasting menu to gain the creative control the concept offers. The price tags for a meal at Charlie Trotter's can be astronomical, but then so is the cost of producing all those complicated little tastes.

Meanwhile, Boston is just beginning to understand prix fixe menus, which offer three courses, for example, at a set price. Often a bargain and sometimes imaginative, prix fixe menus should gain in popularity and sail right into the next century.