|

|

|

|

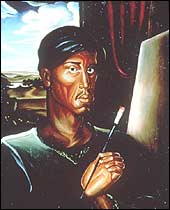

Frederick Flemister, "Man with a Brush" (1940), from "To Conserve a Legacy."

Frederick Flemister, "Man with a Brush" (1940), from "To Conserve a Legacy."

|

his year will go down not only in local museum history, but in the history of museums worldwide, as the year of the second Boston Massacre. This one involved the British director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Malcolm Rogers, abruptly sacking some of the best-loved and most productive curatorial staff at the MFA. Which is bad enough - but obscured the even-worse news that Rogers was rewriting art history to give the architect of the museum's planned expansion, his fellow Brit, Norman Foster, something to design around. ''Something'' turned out to be a few new mega-entities like the Art of Asia and Africa, a union that left art historians and nearly everyone else scratching their heads.

his year will go down not only in local museum history, but in the history of museums worldwide, as the year of the second Boston Massacre. This one involved the British director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Malcolm Rogers, abruptly sacking some of the best-loved and most productive curatorial staff at the MFA. Which is bad enough - but obscured the even-worse news that Rogers was rewriting art history to give the architect of the museum's planned expansion, his fellow Brit, Norman Foster, something to design around. ''Something'' turned out to be a few new mega-entities like the Art of Asia and Africa, a union that left art historians and nearly everyone else scratching their heads.

The Foster master plan, details to be announced in the spring, is one of four major building campaigns in the works at area art museums this year. Harvard University Art Museums director James Cuno has unveiled a plan to have celebrated architect Renzo Piano design a low-lying building, half-hidden by a canopy of trees, on the Charles River site currently occupied by Mahoney's Garden Center on Memorial Drive in Cambridge. The Institute of Contemporary Art won the rights to a choice parcel of land on Boston's Fan Pier, where it plans to build a much-needed new facility. (The ICA has yet to pick an architect.) The Peabody Essex Museum in Salem is expanding its campus and making its jumble of historic buildings more coherent, under a plan by Moshe Safdie. The Peabody Essex project is further along than the others, with $75 million of the anticipated $100 million cost already raised. Other area museums, including the McMullen at Boston College and the Rose at Brandeis University, have also made noises this year about expansion hopes.

Meanwhile, one major building project that had been in the works for more than a decade - the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in the Berkshire town of North Adams - finally opened. It was worth the wait. Several of the abandoned 19th-century brick manufacturing buildings on the 13-acre site have been sensitively restored by Cambridge architects Bruner/Cott + Associates. They now house a yearlong installation of megaworks by the likes of Joseph Beuys, Mario Merz, and Robert Morris, as well as several site-specific commissioned pieces by artists including Germany's Christina Kubisch and Australia's Natalie Jeremijenko. MASS MoCA's visionary and tenacious director, Joseph Thompson, wisely expanded the project to include a black-box theater, a huge outdoor screen that's the end-of-century equivalent of the drive-in movie, and commercial space leased to arts-related tenants. He fought for years to get the state to release the $35 million the Dukakis administration pledged to the museum in 1988. He finally won. And he's been vindicated. Bravo. MASS MoCA helps compensate for the MFA's shenanigans at the other end of the state.

The most surprising exhibition in the Boston area was ''To Conserve a Legacy'' at the Addison Gallery in Andover. Curators Jock Reynolds and Richard Powell put together a project that involved identifying important works in the collections of six historically black US colleges; conserving those works in need of help; writing an extensive and fascinating book about them; and making them into a dazzling show with a national tour of such A-list institutions as the Art Institute of Chicago. This is the caliber of exhibition more museums should have the imagination and ambition to mount.

An admirable and all too rare instance of several museums collaborating occurred with the ''Sargent Summer,'' which included the big ''John Singer Sargent'' retrospective at the MFA, and companion shows of Sargent landscapes at the Gardner and drawings at the Fogg. There was also programming around the Sargent murals at the MFA, which were brilliantly restored in time for the occasion; those at the Boston Public Library, which, alas, were not; and those at Harvard's Widener Library, which are, sadly, inaccessible to the public despite their location just inside the door.

Several Boston cultural institutions are also piggybacking on the MFA's current, and superb, ''Pharaohs of the Sun'' exhibition about Akhenaten, history's first monotheist, and his ''lost'' capital of Amarna. Boston Lyric Opera, for instance, has already offered an ''Aida'' and will stage Philip Glass's ''Akhnaten'' next month. This kind of joint venture is a good model to continue; it can only help bring increased visibility to Boston arts groups in need of it.

Harvard's art museums pride themselves on not doing blockbusters, though this year they lucked into a blockbuster-level donation of major Dutch drawings given by collectors George and Maida Abrams. Harvard specializes in wonderful drawing shows; among this year's was a selection of Ellsworth Kelly's drawings from 1948-1955, the years when he fled America and its overheated Abstract Expressionism and found his own path, the years when Kelly became recognizably Kelly. The genesis of his style, which pays attention to the interstices the rest of us don't notice, was all here.

Like Sargent, the 20th-century American painter Stuart Davis had a particular connection with the Boston area. While he's associated with urban life - especially with Harlem and its jazz culture - he spent nearly 20 summers on Cape Ann, painting Gloucester's harbor, the backyards of its working-class houses, its Portuguese church. ''Stuart Davis in Gloucester,'' at the Cape Ann Historical Museum this summer, showed how Davis progressed from brushy, representational seaside views to hard, bright, enamel-like distillations of sailboats and ocean waves.

Abelardo Morell, the distinguished photographer born in Cuba but now based in Boston (he teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art), was the focus of an important retrospective organized by the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego, which also visited the MFA. Morell's black-and-white photographs make the everyday extraordinary. Whether it's a little boy's shadow or soapy water in a pan, he makes his subjects achingly beautiful. And he makes you see what was there all along. Other than Morell's splendid show, this year's contemporary programming at the MFA was disappointing, centered on recent works by brand-name artists, with little attempt to put them in context.

Morell is one of a group of exceptionally strong photographers now working in the Boston area. Shellburne Thurber is another. ''Home: Photographs by Shellburne Thurber'' at the ICA was a lyrical look at houses so decayed that nature is reclaiming them, their volumes filled with light ranging from a Vermeerlike radiance to blinding.

In this blockbuster-conscious age, artists who are not exactly unknown but also not exactly superstars tend to get overlooked. Thanks to the valiant efforts of curators, sometimes they're not. There were notable cases in point this year. Wadsworth Atheneum director Peter Sutton has spent two decades resurrecting the reputation of Pieter de Hooch, the 17th-century painter who had the misfortune to be the contemporary and neighbor of Vermeer, who has long overshadowed his fellow resident of Delft. Some 315 years after de Hooch's death, Sutton gave him his first solo museum retrospective, a sophisticated look at a painter who, at his best, convinces you that the real world, in all its ordinary details, is a very nice place indeed.

Theodore Stebbins Jr. has been involved with the 19th-century American landscape painter Martin Johnson Heade even longer than Sutton has been involved with de Hooch. Stebbins's Heade exhibition at the MFA is only the third solo show the painter has had, and it's a humdinger. Heade's views are eccentric, never more so than when he went to South America, where he produced the sexiest flowers this side of O'Keeffe and Mapplethorpe. In the midst of his Heade show, Stebbins announced his resignation from the MFA, citing the lack of curatorial opportunities under Rogers's regime.

In picking a Boston College show for a Top 10 list, it's a toss-up this year between the majestic ''Saints and Sinners: Caravaggio and the Baroque Image'' and the provocative ''Irish Art Now.'' The Caravaggio show brought to America a masterpiece recently rediscovered in the Dublin home of some Jesuits who were happy to lend it to their brethren at BC. The painting, ''The Taking of Christ,'' is sublime, one of the very finest of the 50 or so known Caravaggio canvases. The contemporary Irish show, though, ultimately gets my vote for its rigor and avoidance of cliche, thanks to the taste of its curator, Declan McGonagle, a legendary figure in Irish art.

And finally, the end of the year saw a series of stunning installations in area venues, by New York artist Stephen Hendee and Bostonians Denise Marika, Mags Harries, Magdalena Campos-Pons, and Ken Hruby. There was an uncanny formal similarity among the four works by the Boston artists, all with significant objects hovering over pools of various substances on the floor. In Hruby's installation, parachutes bearing videos of idyllic free falls rose slowly into the rafters of the room. The floating action lulled you into a blissful serenity - for a little while. Then, without warning, the chutes crashed. The cruel message I saw in Hruby's installation is that life doesn't work out.