|

Saving the Kattens

The author's great-grandparents and grandmother were trapped in the Third Reich as the Final Solution took shape. It was only the intercession of a US senator from Connecticut that saved their lives.

By Shira Springer, Globe Staff, 7/13/2003

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 Single-page view |

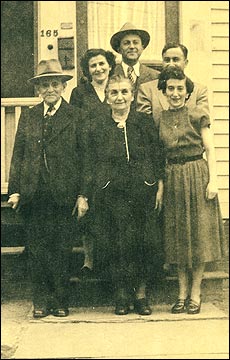

Clockwise from left: Salomon Katten, his daughter Golde Schoen, his sons Siegmund and Al, his daughter Gerda, and his wife, Malchen, in Hartford in 1950, long after their ordeal.

DOCUMENTS

|

he taxi driver drops me off at the Golden Pasture guesthouse, which guards the main entrance to Halsdorf, Germany. In the summer heat, its elderly proprietors and friends sit outside, sipping iced tea and the local brew. They greet my unexpected appearance somewhat suspiciously, though I speak German with a local accent. I introduce myself in the only way that would make sense. "I am Salomon Katten's great-granddaughter," I say without hesitation, though he was betrayed by neighbors in Halsdorf during World War II.

he taxi driver drops me off at the Golden Pasture guesthouse, which guards the main entrance to Halsdorf, Germany. In the summer heat, its elderly proprietors and friends sit outside, sipping iced tea and the local brew. They greet my unexpected appearance somewhat suspiciously, though I speak German with a local accent. I introduce myself in the only way that would make sense. "I am Salomon Katten's great-granddaughter," I say without hesitation, though he was betrayed by neighbors in Halsdorf during World War II.

There is instant recognition of my family, who lived in this agrarian village of half-timbered houses for two centuries. There is also a sudden, solicitous hospitality, but it feels more off-putting than welcoming. The townspeople talk about my grandmother, great-aunts, and great-uncles as if they are still young adults. They recall conversations from several decades earlier. They remember how my grandmother Gerda picked plums from a tree in front of the family's house, how my great-uncle Siegmund served the community as an inventive repairman, how my great-grandfather Salomon carted calves through town in a horse-drawn wagon.

After a half-hour of indulging the townspeople's reminiscences, I am escorted to my family's old house, which remains almost exactly as it was left in 1941. Hilde and Gunther Paesler live in the four-bedroom home. Hilde's mother purchased the house for a fraction of its worth shortly before my grandmother left Halsdorf. My family's only satisfaction from the sale was that the Nazis did not claim it first. I am shown to my grandmother's bedroom, a simple box of a room with white stucco walls and wood furniture.

Hilde and Gunther are eager to please, so they oblige my request to visit the town's Jewish cemetery. During the early years of World War II, Halsdorf was home to approximately 100 families, of which seven were Jewish. The Christian and Jewish communities within Halsdorf kept a socially acceptable distance. Separate cemeteries. Separate schools. Shared general store. Neighborliness was coupled with proper German restraint.

Hilde and Gunther have become default caretakers of the Jewish cemetery, a hilltop plot that is a hike from town. They recognize the names on the list of graves I want to visit. When we arrive at the cemetery, they fill a bucket with soapy water and, though the German couple are in their early 70s, begin to scrub the neglected gravestones I want to see.

amily gatherings are bilingual affairs: German and English. The German conversation is almost always the same, a recounting of who went where during the war and what happened to them, who was saved, who was left behind, who was murdered. There is also always talk about Halsdorf, a story about a nosy neighbor, a funny remembrance about a broken wagon, a reluctant leave-taking. Halsdorf is the town where almost all of my mother's family stories begin and where one chapter of family history met an abrupt end.

amily gatherings are bilingual affairs: German and English. The German conversation is almost always the same, a recounting of who went where during the war and what happened to them, who was saved, who was left behind, who was murdered. There is also always talk about Halsdorf, a story about a nosy neighbor, a funny remembrance about a broken wagon, a reluctant leave-taking. Halsdorf is the town where almost all of my mother's family stories begin and where one chapter of family history met an abrupt end.

The story of US Senator John Danaher of Connecticut was introduced at one such family gathering because it had become inextricably linked to the last months of my family's life in Halsdorf. Since the story has been retold so many times and taken on a mythic quality, I cannot remember exactly when I first learned about Danaher. But his name was always spoken in reverential tones, though we knew little about his isolationist politics, Yale pedigree, or devout Catholicism. It was only clear that my family owed Danaher an immeasurable debt of gratitude. My cousin Ron once remarked, "When Senator Danaher was mentioned, it was like talking about Moses."

he Western Union telegram arrived at 107 Edwards Street in Hartford in January 1940, its urgency evident from the economy of words. "Vater vereist," it read. Literally translated, the message meant, "Father has gone on a trip," but it was actually an unsophisticated code telling family already in America that Salomon Katten had been taken to a concentration camp. The 69-year-old family patriarch had been arrested for a "political offense" several months earlier and detained first at a jail in Marburg, Germany, a city 15 miles from Halsdorf.

he Western Union telegram arrived at 107 Edwards Street in Hartford in January 1940, its urgency evident from the economy of words. "Vater vereist," it read. Literally translated, the message meant, "Father has gone on a trip," but it was actually an unsophisticated code telling family already in America that Salomon Katten had been taken to a concentration camp. The 69-year-old family patriarch had been arrested for a "political offense" several months earlier and detained first at a jail in Marburg, Germany, a city 15 miles from Halsdorf.

No official reason was ever given for his incarceration, though my family suspects Salomon made a flippant remark critical of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis and it was reported to local authorities by a neighbor looking to gain favor. To this day, my family cannot imagine what my great-grandfather might have said. He was a man of simple tastes and steady work habits, apolitical almost to a fault. He was concerned only with the well-being of his family - his wife, Malchen, his two sons, Siegmund and Al, and his two daughters, Golde and Gerda, my grandmother. He was a frail-looking, baldheaded man no taller than 5 feet, with saucer-shaped eyes and a thick mustache that drooped over the corners of his mouth, all of which befit his docile temperament.

My grandmother visited the Marburg prison every day, dutifully taking the hour-long train ride from Halsdorf during the winter of 1939-1940. When the prisoners paraded into public view for morning exercise, she peered down into the prison yard from the third floor of an adjacent apartment building, watching rows of haggard men march past. She waited for Salomon to turn the corner of the far prison wall and come into view. Then, knowing he had not been transferred or suffered a fate far worse, my grandmother caught another train back home.

She took comfort in the routine, until the day she arrived and could not find her father. She scanned the rows of prisoners again and again, hoping the marching order had changed. But Salomon was gone. My grandmother quickly sought sympathetic sources, someone who might know what happened. She knew other men had disappeared from the prison yard to places unknown, never heard from again. My grandmother, however, learned from the local police that Salomon had been transferred to Oranienburg, an early concentration camp just outside Berlin. She immediately alerted family in America with the telegram.

Given the ever-worsening situation for Jews in Germany, it was not a surprising development. Between 1933 and 1939, the Nazi party passed more than 400 laws designed to segregate German Jews as a separate race, depriving them of national citizenship and civil rights and crippling their economic standing within communities. Jewish businesses were forced to close. Jewish doctors could not practice. Jewish travel was severely restricted. Jewish men were forced to adopt the middle name Israel, while Jewish women were forced to take the middle name Sara.

In Halsdorf, a bulletin board in the town center displayed a caricature of Albert Einstein featuring a grossly exaggerated nose. As early as 1933, nearby towns posted signs that read: "Jews Not Welcome Here." Later, my family was forced to vote for Hitler in national elections as Nazi officers watched them sign their ballots. Non-Jews who had helped my great-grandparents harvest crops on the little land they owned stopped coming over. Friends failed to visit. As my great-uncle Al remembers, "You were tolerated, not loved."

My family owned a general store in Halsdorf, and it served as the best local barometer of the German political climate. Because Halsdorf was a rural town removed from the harsher law enforcement found in larger cities and my family provided basic necessities, the store stayed open longer than most other Jewish businesses, despite a declining customer base.

"We had less and less customers coming to the store," my grandmother says. "Some came in the evening when it was dark so that nobody should see them. People were afraid to speak to Jews."

Experiencing the increasing prejudice toward German Jews and fearing much more, my great-grandmother Malchen had enough foresight to make arrangements for her children to emigrate from Germany. In appearance and intellectual interests, Malchen was the opposite of her husband, Salomon. She read voraciously, followed current events, and possessed an astute understanding of national politics. She was short, with an almost stocky build suiting a woman who ran the house and raised four children while her husband fought in the First World War. Her gray-streaked hair was always pulled into a bun, adding to the impression of a stern woman with strong convictions.

My great-grandmother decided that her sons, Siegmund and Al, would leave first, fearing correctly that young men would be imprisoned before others. My great-aunt Golde and her family would go next. My great-grandparents and grandmother would be last, hopefully departing together on the same steamship. And so it was. Almost. Siegmund arrived in America in 1936. Al came in 1937. Golde and her family followed in 1939.

Several months before Salomon was arrested in the fall of 1939, family members already in America had been working relentlessly to gain visas and steamship tickets for my great-grandparents and grandmother. But bureaucracy in Germany and America continually delayed their efforts. Salomon's arrest and transfer to the concentration camp further complicated matters. Siegmund's American wife, my great-aunt Adele, organized, tracked and followed up all attempts to process paperwork for my great-grandparents and grandmother. After she received the news about Salomon being sent to a concentration camp, her correspondence took on a more desperate urgency.

Employed as a secretary for the Herman Rome Co. in Hartford, Adele was tirelessly efficient and adept at dealing with detail. She was meticulous and persistent in her work with such immigration aid organizations as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society, leaving no lead unexplored.

There were weeks on end when her home resembled a small post office, stacks of letters and telegrams being sent and received each day. The backs of calendar pages contained scribbled notes about what she planned to do next. German and English translations of documents and correspondence were kept on smaller, colored scraps of paper. She worked late into the night at the kitchen table until her hands cramped and the typed text blurred.

Inundated with similar requests to help relatives flee Germany, Jewish organizations responded mainly with form letters, sending my family to a different department or different organization. When all other efforts had hopelessly stalled or failed, my great-aunt Adele contacted Senator Danaher. Members of the Hartford Jewish community told her to contact him for the simple reason that he was "someone who helps people." Adele wrote to Danaher, explaining my family's situation and seeking help obtaining visas and steamship tickets for my great-grandparents and grandmother.

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 Single-page view |

![]()

© Copyright 2003 New York Times Company |