|

Saving the Kattens | Continued

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 Single-page view |

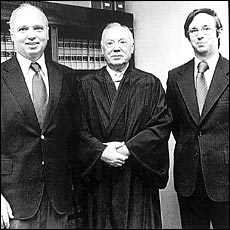

After serving one term in the Senate, John A. Danaher (center) became a judge on the US Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1973, he posed with his grandson R. Cornelius upon his admittance to the Connecticut bar and his Robert C., also a lawyer. (AP Photo)

DOCUMENTS

|

The one condition attached to the sale of my family's home in Halsdorf was that my grandmother be permitted to live there until she could leave Germany. After my great-grandparents departed in late September 1940, my grandmother returned to a home already transformed by the new owners. My grandmother lived almost exclusively in her simple box of a bedroom. But the room was part of an unrecoverable past, and my grandmother felt awkward and out of place, an unwelcome boarder in the only home she had known.

She lived in a reality separate from everyone else in Halsdorf. The townspeople went through their daily routines with only ordinary concerns. Throughout World War II, the idyllic, rolling hills and fertile farmland surrounding Halsdorf buffered the village from harsher realities. My grandmother was largely invisible upon returning to her hometown, shunned by neighbors. Correspondence with family in America provided her only meaningful communication. It proved an unbearably uncomfortable existence. Her stay in Halsdorf lasted only two months. In December 1940, she moved to a pension in Stuttgart. My grandmother was the last Jew to leave Halsdorf.

"Years before, the Nazis broke the windows," she says. "They hated us. We were always happy when the night was over. When I left, I knew I was not coming back."

WASHINGTON

Ever-changing American immigration requirements conspired to keep my grandmother's status in constant doubt. As my great-grandparents sailed to New York, my family was informed that money placed in an irrevocable trust for my grandmother had become insufficient. Senator Danaher was well aware of the capricious application of immigration regulations and the resistance to passing legislation designed to aid refugees.

During his time in the Senate, Danaher saw the Wagner-Rogers Bill, an initiative to admit 20,000 German refugee children outside the quota, die in committee. President Franklin D. Roosevelt took no action on the Wagner-Rogers Bill, personifying the government's indifference in response to the German refugee crisis.

On June 26, 1940, Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long issued a memorandum outlining the delaying tactics American consulates followed during the later half of 1940 and throughout 1941. Long wrote that the State Department could slow immigration "by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way and to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative devices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas."

For many Jews attempting to leave Europe at the time, this postponement policy would become a death sentence.

PORT OF NEW YORK

Upon arriving at the Port of New York, my great-grandparents tearfully fell into the arms of their sons, Siegmund and Al. But the joyful reunion that took four years to arrange was tempered by the absence of my grandmother and the growing fear she would not be able to leave Germany.

The day after my great-grandparents arrived, they were taken to the Hartford National Bank and Trust Co. Based on advice from Senator Danaher, my family learned that increasing my grandmother's financial backing in the United States would improve her immigration status. My family hoped the bank would allow it to transfer money from my great-grandparents' irrevocable trusts to the one in my grandmother's name, though such a transaction was illegal.

HARTFORD

A sympathetic banker suggested a plan. He would withdraw funds from my great-grandparents' trusts and Adele would deposit the money in another local bank for a day. After Adele withdrew the money from the second bank, she would return to the Hartford National Bank and Trust Co. and deposit it into my grandmother's irrevocable trust. To this day, my relatives remain secretive about the lifesaving money transfer, as if they fear repercussions more than 60 years after the fact.

"The issue with the irrevocable trust funds was handled in a manner which would never have been requested, nor granted by the bank, under ordinary circumstances," says Adele. "But these were not ordinary times."

STUTTGART

My grandmother and other German Jews awaiting exit visas were aware of what was happening around Europe at the hands of the Nazis. They received news from daily trips to the local Jewish Center and American Consulate. As the State Department increased requirements for visa applications, fearing German and Russian refugees might be spies, the Nazis relocated hundreds of thousands of Jews from Amsterdam to Vienna, placing them in ghettos, labor camps, and concentration camps in Germany and neighboring countries.

By March 1941, there were 2.1 million Jews trapped within the ghettos of occupied Poland. Also at this time, SS leader Heinrich Himmler ordered Auschwitz enlarged to accommodate tens of thousands of additional prisoners. In the German propaganda film The Eternal Jew, Hitler declared that the current war would lead to the annihilation of the Jews. My grandmother had only to look at her own segregated existence and hear about the conditions of Jews in other countries to recognize what was soon coming to Stuttgart.

Much to her relief, my grandmother received her visa on March 24, 1941. Her quota number, 24158, was called in May. She departed immediately for Portugal, leaving behind her fiance, Julius Levi. By late winter 1941, the two had been engaged for almost a year, but like tens of thousands of other German Jews, Julius could not find a haven or even a way out of Germany. "You must go now," he told my grandmother as they parted. "I will not get out."

LISBON

Since the time my great-grandparents left eight months earlier, steamship arrivals and departures had become unpredictable, and the voyage from Europe to America had become much more dangerous. The fact that my great-grandparents' ship, the Nea Hallas, was torpedoed on its return trip to Lisbon underscored the increasing risk and uncertainty.

After using savings from the sale of the house in Halsdorf to reserve a seat on a direct flight from Germany to Portugal, my grandmother spent four weeks in Lisbon waiting for passage on a ship to America. Every day, my grandmother visited the ticket kiosks operated by the steamship companies, checking the constantly changing departure dates and making sure she could switch ticket reservations made by Adele and Senator Danaher to the first steamship leaving for America. She thought there might not be a second.

In June 1941, my grandmother departed for New York on the Siboney, one of the last passenger ships to leave Europe during the war. The news naturally brought immense relief to my family already in America, and another reunion followed at the Port of New York. When my great-uncles Al and Siegmund brought my grandmother home to her parents and Adele in Hartford, the entire family wept with disbelief and joy.

"What else could you do but try to save your life and get out?" said my grandmother. "I was the last, and thank God I made it, too."

In July 1941, the Nazi regime officially closed all frontiers to Jews and began execution of the Final Solution. In September 1941, all Jews older than 6 were forced to wear yellow stars. In October, Jews needed special permission to leave their houses or use public transportation. All that autumn, the Nazis began transporting Jews to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, which became a way station to Auschwitz. In November, Julius Levi was deported to the Jungfernhof labor camp just outside the Riga ghetto in Latvia. He was later transported to the Stutthof concentration camp.

Recognizing that my grandmother and great-grandparents would not have escaped Germany without the help of Senator Danaher, Adele immediately mailed a letter to Washington expressing my family's gratitude. Upon learning that my grandmother had left Germany with little time to spare, Danaher sent Adele a letter of congratulations. He wrote in typically modest prose and downplayed his essential role:

"I had not the slightest doubt that with the laudable persistence which you have shown you would one day be rewarded and Gerda Katten once more would find a safe haven. Now that that has come to pass and she is here in the United States, I wish to congratulate you and her relatives, and Gerda Katten, especially. If I have contributed in any way toward this result I am more than gratified."

n conversations with my mother, my father frequently mentioned his friendship with a colleague named John. The two men first met on the staff of the Connecticut Law Review in the late 1970s. Then, starting in the fall of 1982, they worked together as associates in the Hartford law offices of Day, Berry and Howard, cooperating on cases as members of the trial department. Since they both began their law careers later than the average attorney and clerked for Connecticut judges, my father and John found much in common.

n conversations with my mother, my father frequently mentioned his friendship with a colleague named John. The two men first met on the staff of the Connecticut Law Review in the late 1970s. Then, starting in the fall of 1982, they worked together as associates in the Hartford law offices of Day, Berry and Howard, cooperating on cases as members of the trial department. Since they both began their law careers later than the average attorney and clerked for Connecticut judges, my father and John found much in common.

One night at home in early 1984, my father called John by his full name, John Danaher. My mother instantly recognized the name, though she did not believe what she heard and did not trust her memory. She immediately called my great-aunt Adele to make sure she correctly remembered the name of the senator who had helped save my great-grandparents and my grandmother. Yes, it was John Danaher. The next day at work, my father asked his friend John if he was related to a former United States senator from Connecticut also named John Danaher. Yes, it was his grandfather.

My family had never met Senator Danaher, though it was soon learned that they had spent decades living only a few miles from each other. But it was the social distance, not the physical distance, that made their meeting unlikely. After serving one term in the US Senate, Danaher became a judge on the US Circuit Court of Appeals and a contender for a seat on the Supreme Court. He received presidential appointments to positions in both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations. He served on the Republican National Committee. He counted former chief justice Warren Burger and the Kennedys among his friends.

Every new appointment or honorary degree Danaher received was met with a prompt congratulatory note by my great-aunt Adele on behalf of my family. Now, my family had an opportunity to thank Danaher in person. A meeting was set for the first Sunday in June 1984.

At 85 years old, Danaher resided in a simple Dutch colonial in West Hartford. My grandmother, great-aunt Adele, and great-uncle Siegmund made the visit, though no one brought a camera to capture the moment for fear of imposing too much. Danaher's wife, Dorothy, served fresh-baked cookies and lemonade with sincere hospitality. But the welcoming and unpretentious atmosphere did not diminish my family's awe.

Danaher listened intently as Adele recounted all the assistance needed to get my family out of Germany and my grandmother recalled the danger she escaped. The visit lasted no more than an hour. It was the first and only time my family met Danaher, though their correspondence continued. A few days after the meeting, Adele received a thank-you note from him dated June 6, 1984:

"Your presence and your personal thanks are all I could possibly desire. Indirectly, I heard you had some other form of acknowledgment in mind. No way, I would say, for our pleasant relationship is all I could possibly permit. I trust that you nice people will find good happiness here in the years ahead."

pilogue: Siegmund, 95, and Adele, 88, live in West Hartford. Adele saved almost all of the letters and telegrams involved in rescuing Salomon, Malchen, and my grandmother Gerda so that future generations could learn what happened.

pilogue: Siegmund, 95, and Adele, 88, live in West Hartford. Adele saved almost all of the letters and telegrams involved in rescuing Salomon, Malchen, and my grandmother Gerda so that future generations could learn what happened.

Gerda, 89, married her fiance, my grandfather Julius, on June 30, 1946, after being kept apart by the Holocaust for nearly five years. At Christmastime, she still exchanges letters with Hilde Paesler of Halsdorf, Germany.

Malchen passed away in 1960 at the age of 87. Salomon passed away in 1966 at the age of 95. The couple's legacy lives on with seven grandchildren, 18 great-grandchildren, and four great-great-grandchildren.

Senator Danaher passed away on September 22, 1990, at the age of 91. Throughout his life, he repeatedly refused any public acknowledgment of the role he played in rescuing my family.

John A. Danaher III lives in the house that once belonged to his grandfather, where the meeting with my family took place. My father's friend John continues the Danaher family tradition of public service, recently serving as US attorney for Connecticut.

My family and the Danahers remain close to this day.

Shira Springer is a member of the Globe staff.

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 Single-page view |

This story ran in the Boston Globe Magazine on 7/13/2003.

© Copyright 2003 Globe Newspaper Company.

![]()

© Copyright 2003 New York Times Company |