|

Saving the Kattens | Continued

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 Single-page view |

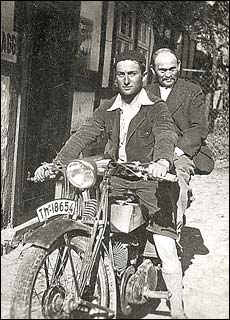

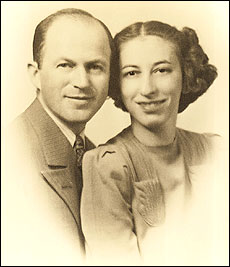

The author's great-uncle and great-aunt Siegmund Kadden (formerly Katten) and his wife, Adele, whose letter-writing efforts were essential in saving her husband's parents and sister.

DOCUMENTS

|

elivering a speech at a communion breakfast at the Hotel Bond in downtown Hartford, Danaher told the rapt audience, "You and I must keep making the right choice, doing the right thing, day in and day out, year after year. Thus we accomplish far more than we suppose and do more good than we realize." It was the clearest, public articulation of his personal philosophy. In a poll of his Senate peers taken in March 1940 that set about picking the "ideal United States senator," Danaher finished second to Robert LaFollette Jr. of Wisconsin, who

had served 15 years at the time. Danaher had served 15 months.

elivering a speech at a communion breakfast at the Hotel Bond in downtown Hartford, Danaher told the rapt audience, "You and I must keep making the right choice, doing the right thing, day in and day out, year after year. Thus we accomplish far more than we suppose and do more good than we realize." It was the clearest, public articulation of his personal philosophy. In a poll of his Senate peers taken in March 1940 that set about picking the "ideal United States senator," Danaher finished second to Robert LaFollette Jr. of Wisconsin, who

had served 15 years at the time. Danaher had served 15 months.

But Danaher was not familiar with all the inner workings of immigration nor the difficulties of arranging travel in war-torn Europe. He offered my family his contacts, the weight of his political position, and unflagging support, though he thought these would be insufficient. In a letter dated April 5, 1940, on the stationery of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Danaher responded to Adele's request for help and wrote that he had "personally contacted the Visa Division of the State Department in their behalf." At the time, the State Department followed rigid and restrictive guidelines regarding emigration from Europe, and Danaher wrote that no government official had the power to waive the 90-day mandatory waiting period for a visa.

Between 1933 and 1938, approximately 40,000 German Jews immigrated to America, a small fraction of those who tried to enter. Popular anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, a residual of the Depression when citizens feared newcomers would take away jobs, made the immigration process difficult. The annual US quota of 27,370 allotted for German and Austrian Jews was never increased and was filled only in 1939. And while Hitler initially encouraged Jews to leave so Germany could become "cleansed of Jews," that policy later changed. By 1940, Jews who could assist the war effort were not allowed to leave, and emigration was virtually impossible for the remaining Jews.

In closing the letter of April 5, 1940, Danaher wrote: "I sincerely regret my inability to be of aid but I trust you will appreciate the circumstances. However, if you feel there is anything further I can do, do not hesitate to advise me. Please believe me with every good wish."

KASSEL, GERMANY

My grandmother approached the Gestapo headquarters, a black overcoat covering her thin, almost frail, diminutive figure. She kept her shoulder-length black hair neatly clipped behind her neck and her brown eyes focused on her destination. It was early April 1940 when my grandmother walked into the brick building with its facade partially obscured by an oversized Nazi flag. She immediately sought an audience with an officer, hoping to plead for my great-grandfather's release from the concentration camp.

A gang of Gestapo officers greeted my grandmother by demanding she turn and face the white corridor wall. "Dreh dich rum," they barked. "Guck mal an der Wand." My grandmother does not remember, or perhaps chooses to forget, the specifics of the degradation and litany of insults that followed. For her, it was a test. For the officers, it was entertainment.

At 26, my grandmother was sufficiently hardened by the injustices and incivilities of the German world around her. She was stoic and stubborn when it came to protecting her parents. Emboldened by her sense of duty, my grandmother told the Nazi officers about her father imprisoned at Oranienburg.

She pleaded. What harm could a 69-year-old cattle dealer do, a German World War I veteran no less? She begged. What could they want with someone who knew little about life outside his small village? Why waste time with an elderly man who only wished to quietly live out his few remaining years? By all appearances unpersuaded, the officers abruptly dismissed my grandmother.

FRANKFURT

When my grandmother returned home, a Jewish neighbor claimed bribery still worked in dealing with the Nazi party. He gave my grandmother the address of a well-to-do Jewish family in Frankfurt. This family had brokered a relationship with a local Nazi in an effort to emigrate from Germany. My grandmother traveled to Frankfurt and gave the family 5,000 marks, the equivalent of approximately $20,000 today. The money was passed along to the Nazi connection. My grandmother never heard anything more from Frankfurt, though she later learned that the well-to-do family itself did not escape Germany in time.

Next, my grandmother contacted the Jewish Hilfsverein in Stuttgart, following another lead that might secure my great-grandfather's release. She repeated the arguments she had made a few weeks earlier to the Nazis in Kassel. The Hilfsverein was dedicated to helping Jews emigrate from Germany, oftentimes negotiating with local Nazi authorities.

STUTTGART

Without notice or explanation, Salomon was freed in late April 1940 and went directly from Oranienburg to Stuttgart, where the American Consulate was located. He contacted my grandmother and great-grandmother, telling them he was free from the concentration camp. My family never learned which of my grandmother's entreaties had worked.

Upon his release, Salomon was told to leave the country within the next several weeks. But the Nazis returned to Halsdorf looking to rearrest him the evening after his release and several times later. Salomon never returned home.

He rented a room in a Stuttgart pension and awaited word about the standing of his immigration papers. Since my great-grandfather did not know when or where the Nazis might again attempt to arrest him, it was an anxious existence, and my great-grandmother would not join him in Stuttgart until absolutely necessary. My grandmother journeyed back and forth from Stuttgart to Halsdorf, making the overnight trip by train at least once a week and sometimes more. The travel was necessary to keep communication discreet and within the family for fear of otherwise alerting the Nazis to Salomon's whereabouts.

Finally, my great-grandparents and grandmother were asked to visit the American Consulate in Stuttgart on July 16, 1940, to pick up visas. The news was greeted cautiously in Germany and America. My great-grandparents and grandmother could not obtain their visas until they presented proof of booked passage to America on a steamship. Conversely, steamship companies were reluctant to book passengers who could not produce proof of exit visas. Many Jewish families waited years for appointments at the American Consulate. If all the paperwork and ticket receipts were not in order, a second chance to collect visas might never come.

HARTFORD

My great-aunt Adele had been working simultaneously on obtaining both visas and tickets. She focused her efforts on a late-September sailing from Yokohama, Japan, to San Francisco, calculating that travel to the Far East would be easier than several border crossings through Europe. Adele repeatedly cabled the American President Lines, inquiring about the availability of tickets. With a week until my great-grandparents and grandmother were scheduled to appear at the American Consulate, they were still waiting to hear from the steamship company. On July 9, Adele informed Danaher of my family's dilemma. She believed the senator's previous personal inquiry into the visas had helped.

"Possibly, if you would contact the American President line, they would take an interest in our case and do everything possible to secure our tickets at once," wrote Adele in a lengthy letter to Danaher. "We realize that there are a lot of people working on this same thing at the present time, but as every day counts now, I am asking you to see if there is anything that you can do for us."

The next day, a Western Union telegram arrived from Washington, D.C. It read: "Have today requested expedited action through local office American President Line. Will keep you advised. John A. Danaher." As the date of my family's appointment at the American Consulate neared, Adele sent a second letter to Danaher.

WASHINGTON

The day before my great-grandparents and grandmother were supposed to visit the American Consulate, Danaher received information from the American President Lines. He sat down in his legislative office suite and wrote an urgent telegram: "San Francisco offers: Room 131 Cleveland sailing September 30 for Katten family." The information was passed along to the American Consulate in Stuttgart.

STUTTGART

But my great-grandparents and grandmother would never board the President Cleveland steamship in Yokahama. They would not even leave Germany at this time. Since citizenship had been revoked for German Jews and they were deemed stateless, my great-grandparents and grandmother were unexpectedly denied Russian transit visas that would have allowed them to ride the trans-Siberian railroad en route to Japan. But even if they were cleared to cross Siberia, my great-grandparents would have had to go alone. While Salomon and Malchen fell into a preferred quota as parents of an American citizen, my great-uncle Siegmund, my grandmother was too old to qualify as a dependent. During her visit to the American Consulate, she was assigned a quota number of lesser priority that would delay the issuance of her visa and her eligibility for entrance into the United States.

HARTFORD

In continued correspondence with Senator Danaher, it was clear by September that my family had reached a pragmatic decision about how immigration efforts would proceed. The fact that my great-grandparents' exit visas would expire at the end of November 1940 and that the Nazis continued to search for Salomon in Halsdorf weighed heavily on all future plans. Adele again supplied Danaher with the personal information necessary for him to help secure tickets on another steamship. Underneath my grandmother's name, Gerda Sara Katten, appeared the annotation "Her ticket could be for a later date, if necessary."

In a letter dated September 4, 1940, Adele informed Danaher that an airline was flying from Germany to Spain, opening the possibility of my great-grandparents departing from Lisbon. It was her desire to book two tickets for an October or November sailing on the Greek liner Nea Hallas. But the steamship company balked at accepting reservations from Jewish German refugees, who faced great obstacles crossing central Europe. It was uncertain whether they would arrive on time, if at all.

Danaher again used his position and influence, personally requesting tickets for my great-grandparents. He frequently acted as a facilitator between my family and the steamship lines, explaining the urgency of my great-grandparents' situation on official Senate stationery. By the end of September, Adele and Danaher secured passage for my great-grandparents aboard the October sailing of the Nea Hallas.

Yet, Adele came close to canceling the tickets on the ship, believing it would be impossible for my great-grandparents to arrive in Lisbon on time. My family in America was uncertain whether the airline flying to Spain would accept Jews, and the price of a flight out of Germany was prohibitive.

STUTTGART

My great-grandparents received financial assistance from the unlikeliest source. Professor Karl Adler, head of the Jewish Hilfsverein in Stuttgart, knew a Nazi willing to aid Jews in their efforts to leave Germany. The Nazi, who wished to remain an anonymous donor, helped pay for the flight. My grandmother took her parents to the airport in Stuttgart and said goodbye, considering only briefly that it might be the last time they saw each other.

"It was the happiest day in my life when I could put my parents in the plane in Stuttgart," said my grandmother. "We had hope that I would get out. I knew they were working hard in America."

Once my great-grandparents had boarded the plane to Spain, it was still uncertain if they would reach Lisbon in time, especially considering the restrictions placed on the flood of refugees then attempting to enter Portugal. Communication with my great-grandparents was impossible as they rushed toward Lisbon.

LISBON

Even after the Nea Hallas set sail, family members in America were unsure if Salomon and Malchen Katten were aboard, whether they should pick them up in New York or work toward booking passage on another steamship. The Nea Hallas departed Lisbon on October 4, 1940, but could not be contacted by radio for four days, until it sailed into international waters and cleared the threat of torpedoes.

On October 8, my great-aunt Adele received the following cable relayed from the Nea Hallas: "Couple Katten proceeded New York."

|

Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 Single-page view |

![]()

© Copyright 2003 New York Times Company |