|

Saving the Kattens

The author's great-grandparents and grandmother were trapped in the Third Reich as the Final Solution took shape. It was only the intercession of a US senator from Connecticut that saved their lives.

By Shira Springer, Globe Staff, 7/13/2003

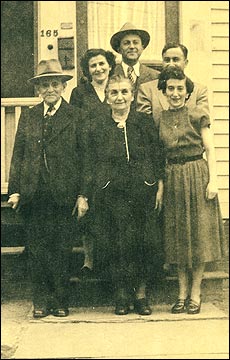

Clockwise from left: Salomon Katten, his daughter Golde Schoen, his sons Siegmund and Al, his daughter Gerda, and his wife, Malchen, in Hartford in 1950, long after their ordeal.

DOCUMENTS

|

he taxi driver drops me off at the Golden Pasture guesthouse, which guards the main entrance to Halsdorf, Germany. In the summer heat, its elderly proprietors and friends sit outside, sipping iced tea and the local brew. They greet my unexpected appearance somewhat suspiciously, though I speak German with a local accent. I introduce myself in the only way that would make sense. "I am Salomon Katten's great-granddaughter," I say without hesitation, though he was betrayed by neighbors in Halsdorf during World War II.

he taxi driver drops me off at the Golden Pasture guesthouse, which guards the main entrance to Halsdorf, Germany. In the summer heat, its elderly proprietors and friends sit outside, sipping iced tea and the local brew. They greet my unexpected appearance somewhat suspiciously, though I speak German with a local accent. I introduce myself in the only way that would make sense. "I am Salomon Katten's great-granddaughter," I say without hesitation, though he was betrayed by neighbors in Halsdorf during World War II.

There is instant recognition of my family, who lived in this agrarian village of half-timbered houses for two centuries. There is also a sudden, solicitous hospitality, but it feels more off-putting than welcoming. The townspeople talk about my grandmother, great-aunts, and great-uncles as if they are still young adults. They recall conversations from several decades earlier. They remember how my grandmother Gerda picked plums from a tree in front of the family's house, how my great-uncle Siegmund served the community as an inventive repairman, how my great-grandfather Salomon carted calves through town in a horse-drawn wagon.

After a half-hour of indulging the townspeople's reminiscences, I am escorted to my family's old house, which remains almost exactly as it was left in 1941. Hilde and Gunther Paesler live in the four-bedroom home. Hilde's mother purchased the house for a fraction of its worth shortly before my grandmother left Halsdorf. My family's only satisfaction from the sale was that the Nazis did not claim it first. I am shown to my grandmother's bedroom, a simple box of a room with white stucco walls and wood furniture.

Hilde and Gunther are eager to please, so they oblige my request to visit the town's Jewish cemetery. During the early years of World War II, Halsdorf was home to approximately 100 families, of which seven were Jewish. The Christian and Jewish communities within Halsdorf kept a socially acceptable distance. Separate cemeteries. Separate schools. Shared general store. Neighborliness was coupled with proper German restraint.

Hilde and Gunther have become default caretakers of the Jewish cemetery, a hilltop plot that is a hike from town. They recognize the names on the list of graves I want to visit. When we arrive at the cemetery, they fill a bucket with soapy water and, though the German couple are in their early 70s, begin to scrub the neglected gravestones I want to see.

amily gatherings are bilingual affairs: German and English. The German conversation is almost always the same, a recounting of who went where during the war and what happened to them, who was saved, who was left behind, who was murdered. There is also always talk about Halsdorf, a story about a nosy neighbor, a funny remembrance about a broken wagon, a reluctant leave-taking. Halsdorf is the town where almost all of my mother's family stories begin and where one chapter of family history met an abrupt end.

amily gatherings are bilingual affairs: German and English. The German conversation is almost always the same, a recounting of who went where during the war and what happened to them, who was saved, who was left behind, who was murdered. There is also always talk about Halsdorf, a story about a nosy neighbor, a funny remembrance about a broken wagon, a reluctant leave-taking. Halsdorf is the town where almost all of my mother's family stories begin and where one chapter of family history met an abrupt end.

The story of US Senator John Danaher of Connecticut was introduced at one such family gathering because it had become inextricably linked to the last months of my family's life in Halsdorf. Since the story has been retold so many times and taken on a mythic quality, I cannot remember exactly when I first learned about Danaher. But his name was always spoken in reverential tones, though we knew little about his isolationist politics, Yale pedigree, or devout Catholicism. It was only clear that my family owed Danaher an immeasurable debt of gratitude. My cousin Ron once remarked, "When Senator Danaher was mentioned, it was like talking about Moses."

he Western Union telegram arrived at 107 Edwards Street in Hartford in January 1940, its urgency evident from the economy of words. "Vater vereist," it read. Literally translated, the message meant, "Father has gone on a trip," but it was actually an unsophisticated code telling family already in America that Salomon Katten had been taken to a concentration camp. The 69-year-old family patriarch had been arrested for a "political offense" several months earlier and detained first at a jail in Marburg, Germany, a city 15 miles from Halsdorf.

he Western Union telegram arrived at 107 Edwards Street in Hartford in January 1940, its urgency evident from the economy of words. "Vater vereist," it read. Literally translated, the message meant, "Father has gone on a trip," but it was actually an unsophisticated code telling family already in America that Salomon Katten had been taken to a concentration camp. The 69-year-old family patriarch had been arrested for a "political offense" several months earlier and detained first at a jail in Marburg, Germany, a city 15 miles from Halsdorf.

No official reason was ever given for his incarceration, though my family suspects Salomon made a flippant remark critical of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis and it was reported to local authorities by a neighbor looking to gain favor. To this day, my family cannot imagine what my great-grandfather might have said. He was a man of simple tastes and steady work habits, apolitical almost to a fault. He was concerned only with the well-being of his family - his wife, Malchen, his two sons, Siegmund and Al, and his two daughters, Golde and Gerda, my grandmother. He was a frail-looking, baldheaded man no taller than 5 feet, with saucer-shaped eyes and a thick mustache that drooped over the corners of his mouth, all of which befit his docile temperament.

My grandmother visited the Marburg prison every day, dutifully taking the hour-long train ride from Halsdorf during the winter of 1939-1940. When the prisoners paraded into public view for morning exercise, she peered down into the prison yard from the third floor of an adjacent apartment building, watching rows of haggard men march past. She waited for Salomon to turn the corner of the far prison wall and come into view. Then, knowing he had not been transferred or suffered a fate far worse, my grandmother caught another train back home.

She took comfort in the routine, until the day she arrived and could not find her father. She scanned the rows of prisoners again and again, hoping the marching order had changed. But Salomon was gone. My grandmother quickly sought sympathetic sources, someone who might know what happened. She knew other men had disappeared from the prison yard to places unknown, never heard from again. My grandmother, however, learned from the local police that Salomon had been transferred to Oranienburg, an early concentration camp just outside Berlin. She immediately alerted family in America with the telegram.

Given the ever-worsening situation for Jews in Germany, it was not a surprising development. Between 1933 and 1939, the Nazi party passed more than 400 laws designed to segregate German Jews as a separate race, depriving them of national citizenship and civil rights and crippling their economic standing within communities. Jewish businesses were forced to close. Jewish doctors could not practice. Jewish travel was severely restricted. Jewish men were forced to adopt the middle name Israel, while Jewish women were forced to take the middle name Sara.

In Halsdorf, a bulletin board in the town center displayed a caricature of Albert Einstein featuring a grossly exaggerated nose. As early as 1933, nearby towns posted signs that read: "Jews Not Welcome Here." Later, my family was forced to vote for Hitler in national elections as Nazi officers watched them sign their ballots. Non-Jews who had helped my great-grandparents harvest crops on the little land they owned stopped coming over. Friends failed to visit. As my great-uncle Al remembers, "You were tolerated, not loved."

My family owned a general store in Halsdorf, and it served as the best local barometer of the German political climate. Because Halsdorf was a rural town removed from the harsher law enforcement found in larger cities and my family provided basic necessities, the store stayed open longer than most other Jewish businesses, despite a declining customer base.

"We had less and less customers coming to the store," my grandmother says. "Some came in the evening when it was dark so that nobody should see them. People were afraid to speak to Jews."

Experiencing the increasing prejudice toward German Jews and fearing much more, my great-grandmother Malchen had enough foresight to make arrangements for her children to emigrate from Germany. In appearance and intellectual interests, Malchen was the opposite of her husband, Salomon. She read voraciously, followed current events, and possessed an astute understanding of national politics. She was short, with an almost stocky build suiting a woman who ran the house and raised four children while her husband fought in the First World War. Her gray-streaked hair was always pulled into a bun, adding to the impression of a stern woman with strong convictions.

My great-grandmother decided that her sons, Siegmund and Al, would leave first, fearing correctly that young men would be imprisoned before others. My great-aunt Golde and her family would go next. My great-grandparents and grandmother would be last, hopefully departing together on the same steamship. And so it was. Almost. Siegmund arrived in America in 1936. Al came in 1937. Golde and her family followed in 1939.

Several months before Salomon was arrested in the fall of 1939, family members already in America had been working relentlessly to gain visas and steamship tickets for my great-grandparents and grandmother. But bureaucracy in Germany and America continually delayed their efforts. Salomon's arrest and transfer to the concentration camp further complicated matters. Siegmund's American wife, my great-aunt Adele, organized, tracked and followed up all attempts to process paperwork for my great-grandparents and grandmother. After she received the news about Salomon being sent to a concentration camp, her correspondence took on a more desperate urgency.

Employed as a secretary for the Herman Rome Co. in Hartford, Adele was tirelessly efficient and adept at dealing with detail. She was meticulous and persistent in her work with such immigration aid organizations as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society, leaving no lead unexplored.

There were weeks on end when her home resembled a small post office, stacks of letters and telegrams being sent and received each day. The backs of calendar pages contained scribbled notes about what she planned to do next. German and English translations of documents and correspondence were kept on smaller, colored scraps of paper. She worked late into the night at the kitchen table until her hands cramped and the typed text blurred.

Inundated with similar requests to help relatives flee Germany, Jewish organizations responded mainly with form letters, sending my family to a different department or different organization. When all other efforts had hopelessly stalled or failed, my great-aunt Adele contacted Senator Danaher. Members of the Hartford Jewish community told her to contact him for the simple reason that he was "someone who helps people." Adele wrote to Danaher, explaining my family's situation and seeking help obtaining visas and steamship tickets for my great-grandparents and grandmother.

elivering a speech at a communion breakfast at the Hotel Bond in downtown Hartford, Danaher told the rapt audience, "You and I must keep making the right choice, doing the right thing, day in and day out, year after year. Thus we accomplish far more than we suppose and do more good than we realize." It was the clearest, public articulation of his personal philosophy. In a poll of his Senate peers taken in March 1940 that set about picking the "ideal United States senator," Danaher finished second to Robert LaFollette Jr. of Wisconsin, who

had served 15 years at the time. Danaher had served 15 months.

elivering a speech at a communion breakfast at the Hotel Bond in downtown Hartford, Danaher told the rapt audience, "You and I must keep making the right choice, doing the right thing, day in and day out, year after year. Thus we accomplish far more than we suppose and do more good than we realize." It was the clearest, public articulation of his personal philosophy. In a poll of his Senate peers taken in March 1940 that set about picking the "ideal United States senator," Danaher finished second to Robert LaFollette Jr. of Wisconsin, who

had served 15 years at the time. Danaher had served 15 months.

But Danaher was not familiar with all the inner workings of immigration nor the difficulties of arranging travel in war-torn Europe. He offered my family his contacts, the weight of his political position, and unflagging support, though he thought these would be insufficient. In a letter dated April 5, 1940, on the stationery of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Danaher responded to Adele's request for help and wrote that he had "personally contacted the Visa Division of the State Department in their behalf." At the time, the State Department followed rigid and restrictive guidelines regarding emigration from Europe, and Danaher wrote that no government official had the power to waive the 90-day mandatory waiting period for a visa.

Between 1933 and 1938, approximately 40,000 German Jews immigrated to America, a small fraction of those who tried to enter. Popular anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, a residual of the Depression when citizens feared newcomers would take away jobs, made the immigration process difficult. The annual US quota of 27,370 allotted for German and Austrian Jews was never increased and was filled only in 1939. And while Hitler initially encouraged Jews to leave so Germany could become "cleansed of Jews," that policy later changed. By 1940, Jews who could assist the war effort were not allowed to leave, and emigration was virtually impossible for the remaining Jews.

In closing the letter of April 5, 1940, Danaher wrote: "I sincerely regret my inability to be of aid but I trust you will appreciate the circumstances. However, if you feel there is anything further I can do, do not hesitate to advise me. Please believe me with every good wish."

KASSEL, GERMANY

My grandmother approached the Gestapo headquarters, a black overcoat covering her thin, almost frail, diminutive figure. She kept her shoulder-length black hair neatly clipped behind her neck and her brown eyes focused on her destination. It was early April 1940 when my grandmother walked into the brick building with its facade partially obscured by an oversized Nazi flag. She immediately sought an audience with an officer, hoping to plead for my great-grandfather's release from the concentration camp.

A gang of Gestapo officers greeted my grandmother by demanding she turn and face the white corridor wall. "Dreh dich rum," they barked. "Guck mal an der Wand." My grandmother does not remember, or perhaps chooses to forget, the specifics of the degradation and litany of insults that followed. For her, it was a test. For the officers, it was entertainment.

At 26, my grandmother was sufficiently hardened by the injustices and incivilities of the German world around her. She was stoic and stubborn when it came to protecting her parents. Emboldened by her sense of duty, my grandmother told the Nazi officers about her father imprisoned at Oranienburg.

She pleaded. What harm could a 69-year-old cattle dealer do, a German World War I veteran no less? She begged. What could they want with someone who knew little about life outside his small village? Why waste time with an elderly man who only wished to quietly live out his few remaining years? By all appearances unpersuaded, the officers abruptly dismissed my grandmother.

FRANKFURT

When my grandmother returned home, a Jewish neighbor claimed bribery still worked in dealing with the Nazi party. He gave my grandmother the address of a well-to-do Jewish family in Frankfurt. This family had brokered a relationship with a local Nazi in an effort to emigrate from Germany. My grandmother traveled to Frankfurt and gave the family 5,000 marks, the equivalent of approximately $20,000 today. The money was passed along to the Nazi connection. My grandmother never heard anything more from Frankfurt, though she later learned that the well-to-do family itself did not escape Germany in time.

Next, my grandmother contacted the Jewish Hilfsverein in Stuttgart, following another lead that might secure my great-grandfather's release. She repeated the arguments she had made a few weeks earlier to the Nazis in Kassel. The Hilfsverein was dedicated to helping Jews emigrate from Germany, oftentimes negotiating with local Nazi authorities.

STUTTGART

Without notice or explanation, Salomon was freed in late April 1940 and went directly from Oranienburg to Stuttgart, where the American Consulate was located. He contacted my grandmother and great-grandmother, telling them he was free from the concentration camp. My family never learned which of my grandmother's entreaties had worked.

Upon his release, Salomon was told to leave the country within the next several weeks. But the Nazis returned to Halsdorf looking to rearrest him the evening after his release and several times later. Salomon never returned home.

He rented a room in a Stuttgart pension and awaited word about the standing of his immigration papers. Since my great-grandfather did not know when or where the Nazis might again attempt to arrest him, it was an anxious existence, and my great-grandmother would not join him in Stuttgart until absolutely necessary. My grandmother journeyed back and forth from Stuttgart to Halsdorf, making the overnight trip by train at least once a week and sometimes more. The travel was necessary to keep communication discreet and within the family for fear of otherwise alerting the Nazis to Salomon's whereabouts.

Finally, my great-grandparents and grandmother were asked to visit the American Consulate in Stuttgart on July 16, 1940, to pick up visas. The news was greeted cautiously in Germany and America. My great-grandparents and grandmother could not obtain their visas until they presented proof of booked passage to America on a steamship. Conversely, steamship companies were reluctant to book passengers who could not produce proof of exit visas. Many Jewish families waited years for appointments at the American Consulate. If all the paperwork and ticket receipts were not in order, a second chance to collect visas might never come.

HARTFORD

My great-aunt Adele had been working simultaneously on obtaining both visas and tickets. She focused her efforts on a late-September sailing from Yokohama, Japan, to San Francisco, calculating that travel to the Far East would be easier than several border crossings through Europe. Adele repeatedly cabled the American President Lines, inquiring about the availability of tickets. With a week until my great-grandparents and grandmother were scheduled to appear at the American Consulate, they were still waiting to hear from the steamship company. On July 9, Adele informed Danaher of my family's dilemma. She believed the senator's previous personal inquiry into the visas had helped.

"Possibly, if you would contact the American President line, they would take an interest in our case and do everything possible to secure our tickets at once," wrote Adele in a lengthy letter to Danaher. "We realize that there are a lot of people working on this same thing at the present time, but as every day counts now, I am asking you to see if there is anything that you can do for us."

The next day, a Western Union telegram arrived from Washington, D.C. It read: "Have today requested expedited action through local office American President Line. Will keep you advised. John A. Danaher." As the date of my family's appointment at the American Consulate neared, Adele sent a second letter to Danaher.

WASHINGTON

The day before my great-grandparents and grandmother were supposed to visit the American Consulate, Danaher received information from the American President Lines. He sat down in his legislative office suite and wrote an urgent telegram: "San Francisco offers: Room 131 Cleveland sailing September 30 for Katten family." The information was passed along to the American Consulate in Stuttgart.

STUTTGART

But my great-grandparents and grandmother would never board the President Cleveland steamship in Yokahama. They would not even leave Germany at this time. Since citizenship had been revoked for German Jews and they were deemed stateless, my great-grandparents and grandmother were unexpectedly denied Russian transit visas that would have allowed them to ride the trans-Siberian railroad en route to Japan. But even if they were cleared to cross Siberia, my great-grandparents would have had to go alone. While Salomon and Malchen fell into a preferred quota as parents of an American citizen, my great-uncle Siegmund, my grandmother was too old to qualify as a dependent. During her visit to the American Consulate, she was assigned a quota number of lesser priority that would delay the issuance of her visa and her eligibility for entrance into the United States.

HARTFORD

In continued correspondence with Senator Danaher, it was clear by September that my family had reached a pragmatic decision about how immigration efforts would proceed. The fact that my great-grandparents' exit visas would expire at the end of November 1940 and that the Nazis continued to search for Salomon in Halsdorf weighed heavily on all future plans. Adele again supplied Danaher with the personal information necessary for him to help secure tickets on another steamship. Underneath my grandmother's name, Gerda Sara Katten, appeared the annotation "Her ticket could be for a later date, if necessary."

In a letter dated September 4, 1940, Adele informed Danaher that an airline was flying from Germany to Spain, opening the possibility of my great-grandparents departing from Lisbon. It was her desire to book two tickets for an October or November sailing on the Greek liner Nea Hallas. But the steamship company balked at accepting reservations from Jewish German refugees, who faced great obstacles crossing central Europe. It was uncertain whether they would arrive on time, if at all.

Danaher again used his position and influence, personally requesting tickets for my great-grandparents. He frequently acted as a facilitator between my family and the steamship lines, explaining the urgency of my great-grandparents' situation on official Senate stationery. By the end of September, Adele and Danaher secured passage for my great-grandparents aboard the October sailing of the Nea Hallas.

Yet, Adele came close to canceling the tickets on the ship, believing it would be impossible for my great-grandparents to arrive in Lisbon on time. My family in America was uncertain whether the airline flying to Spain would accept Jews, and the price of a flight out of Germany was prohibitive.

STUTTGART

My great-grandparents received financial assistance from the unlikeliest source. Professor Karl Adler, head of the Jewish Hilfsverein in Stuttgart, knew a Nazi willing to aid Jews in their efforts to leave Germany. The Nazi, who wished to remain an anonymous donor, helped pay for the flight. My grandmother took her parents to the airport in Stuttgart and said goodbye, considering only briefly that it might be the last time they saw each other.

"It was the happiest day in my life when I could put my parents in the plane in Stuttgart," said my grandmother. "We had hope that I would get out. I knew they were working hard in America."

Once my great-grandparents had boarded the plane to Spain, it was still uncertain if they would reach Lisbon in time, especially considering the restrictions placed on the flood of refugees then attempting to enter Portugal. Communication with my great-grandparents was impossible as they rushed toward Lisbon.

LISBON

Even after the Nea Hallas set sail, family members in America were unsure if Salomon and Malchen Katten were aboard, whether they should pick them up in New York or work toward booking passage on another steamship. The Nea Hallas departed Lisbon on October 4, 1940, but could not be contacted by radio for four days, until it sailed into international waters and cleared the threat of torpedoes.

On October 8, my great-aunt Adele received the following cable relayed from the Nea Hallas: "Couple Katten proceeded New York."

HALSDORF

The one condition attached to the sale of my family's home in Halsdorf was that my grandmother be permitted to live there until she could leave Germany. After my great-grandparents departed in late September 1940, my grandmother returned to a home already transformed by the new owners. My grandmother lived almost exclusively in her simple box of a bedroom. But the room was part of an unrecoverable past, and my grandmother felt awkward and out of place, an unwelcome boarder in the only home she had known.

She lived in a reality separate from everyone else in Halsdorf. The townspeople went through their daily routines with only ordinary concerns. Throughout World War II, the idyllic, rolling hills and fertile farmland surrounding Halsdorf buffered the village from harsher realities. My grandmother was largely invisible upon returning to her hometown, shunned by neighbors. Correspondence with family in America provided her only meaningful communication. It proved an unbearably uncomfortable existence. Her stay in Halsdorf lasted only two months. In December 1940, she moved to a pension in Stuttgart. My grandmother was the last Jew to leave Halsdorf.

"Years before, the Nazis broke the windows," she says. "They hated us. We were always happy when the night was over. When I left, I knew I was not coming back."

WASHINGTON

Ever-changing American immigration requirements conspired to keep my grandmother's status in constant doubt. As my great-grandparents sailed to New York, my family was informed that money placed in an irrevocable trust for my grandmother had become insufficient. Senator Danaher was well aware of the capricious application of immigration regulations and the resistance to passing legislation designed to aid refugees.

During his time in the Senate, Danaher saw the Wagner-Rogers Bill, an initiative to admit 20,000 German refugee children outside the quota, die in committee. President Franklin D. Roosevelt took no action on the Wagner-Rogers Bill, personifying the government's indifference in response to the German refugee crisis.

On June 26, 1940, Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long issued a memorandum outlining the delaying tactics American consulates followed during the later half of 1940 and throughout 1941. Long wrote that the State Department could slow immigration "by simply advising our consuls to put every obstacle in the way and to require additional evidence and to resort to various administrative devices which would postpone and postpone and postpone the granting of visas."

For many Jews attempting to leave Europe at the time, this postponement policy would become a death sentence.

PORT OF NEW YORK

Upon arriving at the Port of New York, my great-grandparents tearfully fell into the arms of their sons, Siegmund and Al. But the joyful reunion that took four years to arrange was tempered by the absence of my grandmother and the growing fear she would not be able to leave Germany.

The day after my great-grandparents arrived, they were taken to the Hartford National Bank and Trust Co. Based on advice from Senator Danaher, my family learned that increasing my grandmother's financial backing in the United States would improve her immigration status. My family hoped the bank would allow it to transfer money from my great-grandparents' irrevocable trusts to the one in my grandmother's name, though such a transaction was illegal.

HARTFORD

A sympathetic banker suggested a plan. He would withdraw funds from my great-grandparents' trusts and Adele would deposit the money in another local bank for a day. After Adele withdrew the money from the second bank, she would return to the Hartford National Bank and Trust Co. and deposit it into my grandmother's irrevocable trust. To this day, my relatives remain secretive about the lifesaving money transfer, as if they fear repercussions more than 60 years after the fact.

"The issue with the irrevocable trust funds was handled in a manner which would never have been requested, nor granted by the bank, under ordinary circumstances," says Adele. "But these were not ordinary times."

STUTTGART

My grandmother and other German Jews awaiting exit visas were aware of what was happening around Europe at the hands of the Nazis. They received news from daily trips to the local Jewish Center and American Consulate. As the State Department increased requirements for visa applications, fearing German and Russian refugees might be spies, the Nazis relocated hundreds of thousands of Jews from Amsterdam to Vienna, placing them in ghettos, labor camps, and concentration camps in Germany and neighboring countries.

By March 1941, there were 2.1 million Jews trapped within the ghettos of occupied Poland. Also at this time, SS leader Heinrich Himmler ordered Auschwitz enlarged to accommodate tens of thousands of additional prisoners. In the German propaganda film The Eternal Jew, Hitler declared that the current war would lead to the annihilation of the Jews. My grandmother had only to look at her own segregated existence and hear about the conditions of Jews in other countries to recognize what was soon coming to Stuttgart.

Much to her relief, my grandmother received her visa on March 24, 1941. Her quota number, 24158, was called in May. She departed immediately for Portugal, leaving behind her fiance, Julius Levi. By late winter 1941, the two had been engaged for almost a year, but like tens of thousands of other German Jews, Julius could not find a haven or even a way out of Germany. "You must go now," he told my grandmother as they parted. "I will not get out."

LISBON

Since the time my great-grandparents left eight months earlier, steamship arrivals and departures had become unpredictable, and the voyage from Europe to America had become much more dangerous. The fact that my great-grandparents' ship, the Nea Hallas, was torpedoed on its return trip to Lisbon underscored the increasing risk and uncertainty.

After using savings from the sale of the house in Halsdorf to reserve a seat on a direct flight from Germany to Portugal, my grandmother spent four weeks in Lisbon waiting for passage on a ship to America. Every day, my grandmother visited the ticket kiosks operated by the steamship companies, checking the constantly changing departure dates and making sure she could switch ticket reservations made by Adele and Senator Danaher to the first steamship leaving for America. She thought there might not be a second.

In June 1941, my grandmother departed for New York on the Siboney, one of the last passenger ships to leave Europe during the war. The news naturally brought immense relief to my family already in America, and another reunion followed at the Port of New York. When my great-uncles Al and Siegmund brought my grandmother home to her parents and Adele in Hartford, the entire family wept with disbelief and joy.

"What else could you do but try to save your life and get out?" said my grandmother. "I was the last, and thank God I made it, too."

In July 1941, the Nazi regime officially closed all frontiers to Jews and began execution of the Final Solution. In September 1941, all Jews older than 6 were forced to wear yellow stars. In October, Jews needed special permission to leave their houses or use public transportation. All that autumn, the Nazis began transporting Jews to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, which became a way station to Auschwitz. In November, Julius Levi was deported to the Jungfernhof labor camp just outside the Riga ghetto in Latvia. He was later transported to the Stutthof concentration camp.

Recognizing that my grandmother and great-grandparents would not have escaped Germany without the help of Senator Danaher, Adele immediately mailed a letter to Washington expressing my family's gratitude. Upon learning that my grandmother had left Germany with little time to spare, Danaher sent Adele a letter of congratulations. He wrote in typically modest prose and downplayed his essential role:

"I had not the slightest doubt that with the laudable persistence which you have shown you would one day be rewarded and Gerda Katten once more would find a safe haven. Now that that has come to pass and she is here in the United States, I wish to congratulate you and her relatives, and Gerda Katten, especially. If I have contributed in any way toward this result I am more than gratified."

n conversations with my mother, my father frequently mentioned his friendship with a colleague named John. The two men first met on the staff of the Connecticut Law Review in the late 1970s. Then, starting in the fall of 1982, they worked together as associates in the Hartford law offices of Day, Berry and Howard, cooperating on cases as members of the trial department. Since they both began their law careers later than the average attorney and clerked for Connecticut judges, my father and John found much in common.

n conversations with my mother, my father frequently mentioned his friendship with a colleague named John. The two men first met on the staff of the Connecticut Law Review in the late 1970s. Then, starting in the fall of 1982, they worked together as associates in the Hartford law offices of Day, Berry and Howard, cooperating on cases as members of the trial department. Since they both began their law careers later than the average attorney and clerked for Connecticut judges, my father and John found much in common.

One night at home in early 1984, my father called John by his full name, John Danaher. My mother instantly recognized the name, though she did not believe what she heard and did not trust her memory. She immediately called my great-aunt Adele to make sure she correctly remembered the name of the senator who had helped save my great-grandparents and my grandmother. Yes, it was John Danaher. The next day at work, my father asked his friend John if he was related to a former United States senator from Connecticut also named John Danaher. Yes, it was his grandfather.

My family had never met Senator Danaher, though it was soon learned that they had spent decades living only a few miles from each other. But it was the social distance, not the physical distance, that made their meeting unlikely. After serving one term in the US Senate, Danaher became a judge on the US Circuit Court of Appeals and a contender for a seat on the Supreme Court. He received presidential appointments to positions in both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations. He served on the Republican National Committee. He counted former chief justice Warren Burger and the Kennedys among his friends.

Every new appointment or honorary degree Danaher received was met with a prompt congratulatory note by my great-aunt Adele on behalf of my family. Now, my family had an opportunity to thank Danaher in person. A meeting was set for the first Sunday in June 1984.

At 85 years old, Danaher resided in a simple Dutch colonial in West Hartford. My grandmother, great-aunt Adele, and great-uncle Siegmund made the visit, though no one brought a camera to capture the moment for fear of imposing too much. Danaher's wife, Dorothy, served fresh-baked cookies and lemonade with sincere hospitality. But the welcoming and unpretentious atmosphere did not diminish my family's awe.

Danaher listened intently as Adele recounted all the assistance needed to get my family out of Germany and my grandmother recalled the danger she escaped. The visit lasted no more than an hour. It was the first and only time my family met Danaher, though their correspondence continued. A few days after the meeting, Adele received a thank-you note from him dated June 6, 1984:

"Your presence and your personal thanks are all I could possibly desire. Indirectly, I heard you had some other form of acknowledgment in mind. No way, I would say, for our pleasant relationship is all I could possibly permit. I trust that you nice people will find good happiness here in the years ahead."

pilogue: Siegmund, 95, and Adele, 88, live in West Hartford. Adele saved almost all of the letters and telegrams involved in rescuing Salomon, Malchen, and my grandmother Gerda so that future generations could learn what happened.

pilogue: Siegmund, 95, and Adele, 88, live in West Hartford. Adele saved almost all of the letters and telegrams involved in rescuing Salomon, Malchen, and my grandmother Gerda so that future generations could learn what happened.

Gerda, 89, married her fiance, my grandfather Julius, on June 30, 1946, after being kept apart by the Holocaust for nearly five years. At Christmastime, she still exchanges letters with Hilde Paesler of Halsdorf, Germany.

Malchen passed away in 1960 at the age of 87. Salomon passed away in 1966 at the age of 95. The couple's legacy lives on with seven grandchildren, 18 great-grandchildren, and four great-great-grandchildren.

Senator Danaher passed away on September 22, 1990, at the age of 91. Throughout his life, he repeatedly refused any public acknowledgment of the role he played in rescuing my family.

John A. Danaher III lives in the house that once belonged to his grandfather, where the meeting with my family took place. My father's friend John continues the Danaher family tradition of public service, recently serving as US attorney for Connecticut.

My family and the Danahers remain close to this day.

Shira Springer is a member of the Globe staff.

This story ran in the Boston Globe Magazine on 7/13/2003.

© Copyright 2003 Globe Newspaper Company.

![]()

© Copyright 2003 New York Times Company |